What Baseball Does to the Soul

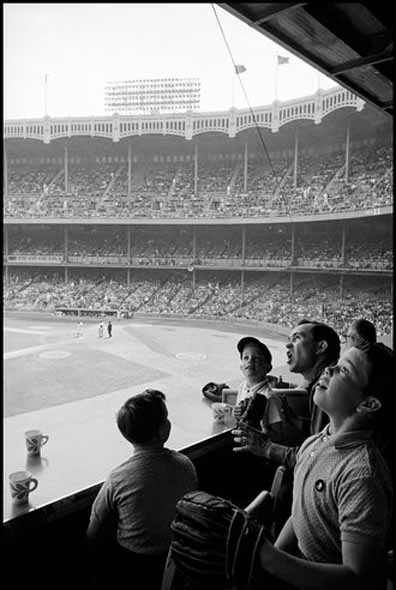

New York City, 1962, Yankee Stadium. Credit Inge Morath/The Inge Morath Foundation — Magnum Photos

IT was long before baseball ever enchanted me, and long before I ever knew anything of the Yankees, and long before I learned that a pitch could swerve, yet it came back to me, years later, sitting in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium, a curveball from the past.

It was 1975. I was 10 years old. I stood onboard a ferry in Dun Laoghaire, Ireland. I was traveling with my father to England for the weekend. We crossed the Irish Sea, the night blanket-black above us. On deck, men in flat caps worked hard at their coughs.

In Liverpool, dawn rose in increments of gray. We boarded a train for London. I had to hush. We were Irish after all. There were bombs going off in Britain in those days. The train swerved through a landscape that seemed exotic and familiar by turns. London, then, was a confusion of red post boxes, terraced houses and chimneystacks.

We made our way out to Highbury, where my favorite team, Stoke City, was playing against Arsenal. Portions of the game still decorate my memory with splinters of despair and joy — my team drew, 1-1 — but it is not the game that later made sense to me.

On the way out of Highbury, my father and I bought a bottle of Powers whiskey. He seldom drank, my father, and the purchase surprised me. We stopped, then, to buy a carton of cigarettes and I knew that the world was shifting somehow: my father never smoked.

“How’d you like to see your grandfather?” he asked.

I had never met my grandfather Jack McCann. He was, I knew, a character — a man given to the Irish trinity of drink and song and exile.

We took a bus to Pimlico Road, tramped up the wide staircase of a decrepit nursing home. My father handed me the bottle of whiskey. “Go on in and give that to your grandda,” he said.

A shadow in the bed. He glanced up and said, “Ah, another bleedin’ McCann.” But he perked up when he saw the bottle, reached out and tousled my hair.

He was a fabulous ruin, my grandfather. I sat on the bed beside him and — suddenly glamorous with whiskey — he told his stories. The greyhounds. The horses. The days with Big Jack Doyle. I sat in my red and white Stoke City shirt, stunned that this was a history that could belong to me.

What I recall is my father lifting me onto his shoulders, late that night, into a foreign city, toward the railway station, and home. A number of stray soccer fans were still singing under the station’s eaves.

Down, 3-1. Bottom of the ninth. One on. Nobody out. The Yankees against the Minnesota Twins. Game 2 of the American League Division Series, October 2009. A-Rod is at the plate. The air has that chewy sense of hope. There is always call for a miracle.

“It’s gonna happen, Dad.”

This is what baseball can do to the soul: it has the ability to make you believe in spite of all other available evidence. My son, John Michael, is 10 years old. We are in the bleachers. He leans in to me and says that the pitch is going to come in high and fat. It’s still a new language to me. The pitch is thrown, and indeed it does — it comes in high and fat, and 94 miles per hour. A-Rod leans into it like he’s about to fell a tree and smacks the ball and it soars, that little sphere of cowhide rising up over the Bronx, and it is a moment unlike any other, when you sit with your son in the ballpark, and the ball is high in the air, you feel yourself aware of everything, the night, the neon, the very American-ness of the moment.

And then it strikes you that the ball has an endless quality of fatherhood to it.

We all know these moments. They don’t come along very often, but when they do they open up your lungs to the bursting point. It’s not simply me sitting with my son in the Bronx, but it’s my father sitting with me in London, too, and maybe him with his own father in Dublin, and it all comes back to me, the pure and reckless joy of the past, Arsenal, Stoke City, the dark corners of a nursing home, the slippery deck of a ferry boat and how every moment is carried into other moments.

I stood in the bleachers as A-Rod rounded the bases with that slightly nonchalant grin: a Dominican kid born in Washington Heights had just brought me home.

Baseball is often talked about as the American game, but there is something wildly immigrant about it too. No other game can so solidly confirm the fact that you are in the United States, yet bring you home to your original country at the same time.

If soccer is the world’s game, then baseball belongs to those who have left their worlds behind. This is not so much nostalgia as it a sense of saudade — a longing for something that is absent.

I have been in New York for 18 years. Every time I have gone to Yankee Stadium with my two sons and my daughter, I am somehow brought back to my boyhood. Perhaps it is because baseball is so very different from anything I grew up with.

The subway journey out. The hustlers, the bustlers, the bored cops. The jostle at the turnstiles. Up the ramps. Through the shadows. The huge swell of diamond green. The crackle. The billboards. The slight air of the unreal. The guilt when standing for another nation’s national anthem. The hot dogs. The bad beer. The catcalls. Siddown. Shaddup. Fuhgeddaboudit.

Learning baseball is learning to love what is left behind also. The world drifts away for a few hours. We can rediscover what it means to be lost. The world is full, once again, of surprise. We go back to who we were.

I slipped into America via baseball. The language intrigued me. The squeeze plays, the fungoes, the bean balls, the curveballs, the steals. The showboating. The pageantry. The lyrical cursing that unfolded across the bleachers.

As the years went on, baseball surrounded me more and more. My son began listening to the radio late at night, under the covers. There was something gloriously tribal about the Yankees for him. He learned to imitate John Sterling, the radio announcer. It is high, it is far, it is gone. An A-bomb from A-Rod. He began playing the game too, and so I would walk to Central Park with him. How far was my own father on the street behind me, juggling a soccer ball at his feet? How far was my dead grandfather?

We become the children of our children, the sons of our sons. We watch our kids as if watching ourselves. We take on the burden of their victories and defeats. It is our privilege, our curse too. We get older and younger at the same time.

I never meant to fall in love with baseball, but I did. I learned to realize that it does what all good sports should do: it creates the possibility of joy.

Sometimes, when walking home from the subway, after being at Yankee Stadium, I have the feeling that a whole country has been knocked around inside me. I am Irish, but I am also American. I am both father and son.

I cherish these moments. It confirms that life is not static. There is so much more left to be lived. There are times that my own boys are so tired that I have to put them on my shoulder and carry them. They are brought forward by the past.

I still recall the night of the A.L.D.S. game against Minnesota. A-Rod tied it up in the ninth. Teixeira closed out the game in the 11th. My son beamed, ear to ear. I think the stars over the Bronx shook that night. The potholes on 161st Street applauded. The 4 train ran on Champagne.

And me, well, I took a little journey a long way home.

This article was originally published in The New York Times on March 30, 2012