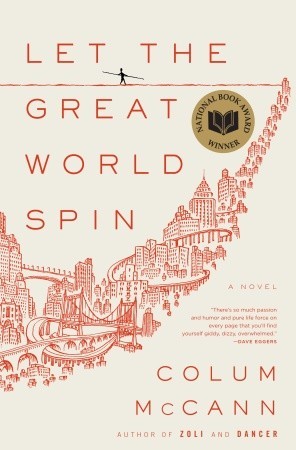

Let The Great World Spin Q&A

Tell us about your new novel, Let the Great World Spin.

Well, on one hand it is a simple narrative of lives entwined in the early 1970’s. Most of it takes place on one day in New York in August 1974 when Phillipe Petit (unnamed in the book) makes his tightrope walk across the World Trade Center towers, a walk that was called “the artistic crime of the 20 th century.”

Instead of focussing on Petit, however, the book follows the intricate lives of a number of different people who live on the ground, or, rather, people who walk the ground’s tightrope. They accidentally dovetail in and out of each other’s lives on this one day – an Irish monk living in the housing projects, a Park Aveneu mother of a Vietnam vet/computer expert, a 38-year-old hooker in the Bronx, an errant artist who has lost her way, a subway tagger and so on. The lives braid in and out of each other. It’s a collision, really, a web in this big sprawling complex web that we call New York. A French editor has described the book as a sort of “New York Ulysses,” and maybe it fits in the sense that it mostly takes place on one day, and that it embraces the intricacy of the ordinary, but I’m very wary of the comparison of course, there’s only one Ulysses.

It’s also a social novel that looks at the ongoing nature of our lives, how the accidental meets the eternal. And it functions as a 9/11 allegory. The book leapfrogs forward to 2006, where the present meets the past, and questions it, even authenticates it. I suppose it’s a novel that tries to uncover joy and hope and a small glimmer of grace. I’d argue that sort of sentiment necessary these days. You also want it to be a rollicking good story. You want it to break hearts. You want people to finish the story and then immediately want to begin it again.

And maybe it’s just a novel about the polyphonic city … my love letter to old New York in all her clothes, shabby and dignified both.

Let the Great World Spin spans so many nooks and crannies of New York City – what research did you do for this book, for instance to learn about prostitutes in the Bronx?

Do you really want to know?! I have a bit of an errant imagination, I suppose. That’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it!

Seriously, for many months I tried to imagine the life of Tillie – the 38 year old grandmother/hooker — but her voice was elusive. I read a lot. I watched some movies and documentaries. I went out on the beat with a lot of cops, including homocide detectives. Out in their squad cars. It was wild. We even copped what we thought was a murder one night, but it turned out to be something else, a guy who blew his heart out with cocaine. But I saw my first dead body in the “field” – a strange and disconcerting sight.

Of course research is only that – background music. There are no detectives in the book, really, but they gave meimaginative access, even though we’re talking about trying to imagine 35 years ago. I looked a rap sheets, street stories, hung out on street corners, tried to imagine the world four decades ago. I chatted to some older women who knew the times. I did a little research in the library, watched films, looked at photos. I love photos, you can step right into them. They are like tiny novels, each of them.

I also enjoyed finding out about the hackers (the computer programmers) of the early 70’s. I’m hoping to get a copy of my book to Bill Gates … he was one of the early hackers in the 70’s. He was one of the pioneers of the blue box program that’s at the centre of one of the chapters.

There is an enormous cast of characters – an incredible variety of voices – in this novel. Who was your favorite to write? Any that did not come easily?

It all started out with Corrigan, although his story is narrated by his brother. And the voices grew from Corrigan. He contains all these other voices. He introduced me to all the others, so he was my fulcrum voice.

I was interesed in ideas of faith, art, poverty. But then there was another thread I wanted to go for, the wealth and the technology, and the voices that might accompany this, and a sneaky favourite of mine is the wealthy Park avenue mother, Claire. Don’t tell anybody … but I also live on NY’s Upper east Side. The area has got the worst rap in the city really – everyone finds it diseased with all this WASPy mentality, all old money and colonial furniture. But nothing is ever exactly what it seems … and again I was more interested in finding out what goes on behind the curtains. She came to me already fully formed. I knew her. And I ended up loving her, her broken-ness. I think she’s true. I have a feeling that a lot of Upper East Side women will like her, and maybe even feel represented in the fact that she’s not a cliché, at least I hope not.

Much of your fiction engages issues of social class and the working poor, including this one; do you consider this a political novel, or yourself a political writer?

Yes. And yes.

It sometimes seems to me that the contemporary social novelist has muzzled himself or herself a bit in recent years. There is a fear of seeming too engaged. Acrisis of disengagement. We want our novels, our screen plays, our plays untainted by politics. We don’t want history or social activism. We don’t need somebody else telling us how to live, since yet another politician is more than we can stomach. For some people, there is the air of the impure about the social novel — it is nearly always seen as ideological, or political, and therefore limited. I don’t see it that way. I see the social novel as an open text, an open field for us to step into, and maybe breathe in a new air. But it’s up to the reader to make sense of this. A novel has to be left open, so a reader can step inside. It’s not up to me to tell people how to think. I paint a photograph, if you will, and then other people inhabit it. I’m nothing without a good reader.

The World Trade Center at this point is quite a loaded symbol; would you call this book a 9/11 allegory?

Intentionally so, yes. In fact 9/11 was the initial impetus for the book – my question to myself was: How do we talk about these things? But I am aware of the pitfalls of labelling it a “9/11 novel,” especially for American readers many of whom, like me, are tired of the idea of a 9/11 genre. But it has to be looked at. And 9/11 is certainly part of the book’s construction, but it is not limited to that. But in this sense it is very much a book of hope and in some ways it’s an anti-9/11 novel. 9/11 is not mentioned (or at least it is only mentioned glancingly, in a single sentence, towards the end). But I think it’s vital that it at least be part of the novel, in the sense that the novel is multi-faceted and multi-themed.

But I really wanted to lift it out of the 9/11 “grief machine.” One can read it on all sorts of levels.

My father-in-law Roger Hawke was one of the lucky ones, he got out on 9/11. He was working (as a lawyer) on the 59 th floor and got out with just a few moments to spare. And he walked uptown to the apartment where my wife and I were living, and he was covered in dust, and I remember my daughter Isabella smelling the smoke off his clothes and she said: ‘Poppy’s burning,’ and I said, ‘No, no, love, it’s just the smoke on his clothes from the buildings,’ and she said — out of the mouths of babes—‘No, no, he’s burning from the inside out.’ And it struck me immediately that she was talking about a nation. Or that’s what I thought at first anyway. She’s right, we’re burning from the inside out.

And I began to wonder, Who’s going to write about this? I did some essays for newspapers and so on, but so many writers did, I certainly wasn’t unique, we all needed to get at the heart of it. Susan Sontag was the bravest of all. But every piece was poignant: every journalist, every poet, every gossip even. Even the wags on the corner. And everything had meaning: it was like the whole city was infused with meaning. The lone fire hydrant. The flowers on the window of a car. A bit of ash that tickled the back of your throat. You couldn’t help thinking that everything held importance. Even the child’s painting of the two buildings holding hands was a powerful image. In fact, it was a level ground of meaning. Meaning came down, it was leveled into dust. The overworld, the underworld.

I felt it was quite impossible to write something that would break your heart, because anyone with any sort of heart had it broken that morning. And I’m not just talking about the hands-on grief, that look-at-me-I’m-burning sort of grief, I’m talking about what it meant for the world, the horrors that the Bush administration would unfold in its name, the terrible way they turned justice into revenge, the dark mark of hatred that reared itself both in the Islamic world and in Britain and here in the States. I mean, I just recall being so very hopeful for the first few days, thinking that maybe now we would understand grief, maybe we could be empathetic, maybe we could turn some good out of this. But then the months went on and it kept getting worse, until of course they unfolded the map of Iraq to level it, and it turned into a tragedy of Shakespearian proportions. And still the question was: how do I write about this? How do I get from one end of the tightrope to the other?

I remembered the Petit walk pretty early on, and I knew that was my novel—that had to be it. Originally I was just going to write the novel and have him fall, mess with history, the facts, the textures. I was raring to go. But I had already embarked on Zoli and I wasn’t willing to throw all that work away, so I tucked the Petit thing in the idea drawer. Not that it’s a tremendously original idea anyway. First of all, he did the walk. He himself wrote a book about it after the towers came down. Then came a children’s book. Then a play. Then a documentary. I mean, it’s the obvious image. I’m not exactly at the edge. But I couldn’t deny the power of the image.

It was even on the cover of the September 11 thNew Yorker on the fifth anniversary.

Yes, that great drawing where the city becomes a ghost at his feet. The walk across the World Trade works on so many levels, it even has that Nietzschian ring to it, the over-man stuff. But I always that at the heart of my novel it wouldn’t be ‘about’ Petit’s walk. I knew I was writing a 9/11 novel, one written in advance. But it was an emotional response, rather than a measured intellectual one. And the fact that all this stuff took place thirty years ago was perfect, because I could lay it over the present, like tracing paper. And let the reader decide. And my benchmark was my father in law. He couldn’t stomach anything about 9/11. He hated the books and the screenplays and the ra-ra-ra industry that grew up around it, the missiles slammed into Baghdad in defense of greed, he was, like a lot of Americans, disgusted by it all. He woke at night dreaming of those young firemen running up the stairs past him while he escaped. He said he’d never read a 9/11 novel. But he eventually read mine and he knew what was going on with it, he felt it, he felt all that grief, and yet it’s exactly as you say, he recognised immediately that it was a novel about creation, maybe even a novel about healing in the face of all the evidence. He liked it. In many ways, it’s his book. It’s my response to him. Look at that, you’re alive, your grandkids are jumping in your lap. This is powerful stuff to me. This is the glue. This is what we were meant for.

I was never conscious until I’d finished the novel that I had Corrigan and Jazzlyn (two of the main characters) becoming two towers. Small and ordinary towers, I suppose, those lives that fall. And they are the only ones who never get to tell their stories. Everyone else tells the story for them. But they go on living. This, I suppose, is the art of how we come to survive.

So I think in many ways it is a book about healing, and about moving on even in the most difficult times. We recover.

Then in another respect it’s just a novel about the 70’s – that mad, wonderful time in our history. Flared jeans, shaggy hair, disco lights, that sort of thing. But even then the questions were the questions we have now …. Soldiers coming home from the war, questions of technology, questions of faith, questions of belonging and the ultimate question of WILL WE FALL? In fact the two times – now and ’74 – fold over onto each other in all sorts of extraordinary ways. So the novel is about NOW but in the guise of long ago.

And then again it could just be what Faulkner says every novel should be about, and that’s the complications of the human heart …

Another thing that maybe this novel anticipates, or reflects perhaps, is the Obama era.

The last chapter is very much a metaphor for the Obama years and the promise of being able to break from the past.

What other writers influenced Let the Great World Spin?

I’m always dubious about comparing it to other writers, just of becase who I will obviously forget, I’m a bit of a throwback to the old Steinbeck social novel, maybe even the Dresier mould.

And contemporary influences?

I don’t know, it might be an idea to talk about DeLillo, Berger, Doctorow, I feel embarrassed even bringing up their names. My own colleague (at Hunter College), Peter Carey. Jim Harrison. They’re big and brave. Among the younger writers I admire are Aleksandar Hemon, Zadie Smith, Dave Eggers, Junot Diaz, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Nathan Englander and dozens more, so many more, John Wray, Marlon James, Darrin Strauss, David Mitchell, Kamile Shamsie, Joseph O’Connor, Gary Shteyngart, Jeff Talargio, just shut me up when I begin to read the roll-call: but these ARE great writers and they tend to look at the big issues, and are brave in what they want to confront. I hate doing lists because I know that I forget people then I remember them five minutes later and I think …. Well …

Has Petit read or responded to your book?

Phillippe is a very private man by all accounts. I respect that. I sent him the book. I have no idea how he felt. But the story of the book – which I know he must recognise – is that we are all fumnamblists. He did his walk high in the air. I try mine on the page. My characters tightrope the street. We are connected.

Did you have fun writing this book?

I loved it, it was a great time, though if you asked me that question while I was writing it I know my answer would be different. But every time I get to a new novel I feel like I’m in university again. Holes in my jeans. No money in my pockets. The promise of finding out something new. This is the beauty of story-telling or story-making … all those journeys we’ve not yet taken.

And the next one?

Don’t know. I’m recovering from the exhaustion of this one. I put everything into it. I need to build up my stocks again. I’m terrified really, to tell the truth. But I always feel this way … and then the stories start to come. I’m listening again. Nothing better than that knife-edge.