The Music of What Happens

Imagine this: It is August, 1950. He is Irish. He is in London. He is engaged to be married in Westminster Church to a pretty farm-girl from Northern Ireland. He tells her in love letters that her beauty paints the world well. Shortly before the wedding she gets cold feet. She cancels the service. In his grief and confusion he joins the British Air Force and gets sent to Egypt as an intelligence officer.

Six months pass. He writes to her every day. She takes a seven-day boat journey to Port Said where he meets her on the docks, takes her hand, spins her in the air. Together they defy curfew so she can find a place to get her wedding dress ironed.

They marry in a Catholic church in Cairo the next day. It is a hundred and six degrees in the reception tent. A light wind blows and the torn flap of the tent applauds.

It is a story will bind them together for the next sixty-four years.

Our stories are the glue of what we are. They stitch together what we become. It is our ability to tell these stories that is fundamental to how we celebrate and examine our lives.

After we have satisfied the need for water, food, a roof, and companionship, story-telling is the thing we go to most for encouragement in how to live. We search for the affirmation of our joy and sometimes even our despair. We find something to believe in. We discover a way to make sense of the roulette of the world.

Stories are the most common things we have in this world, and yet we tell them precisely because our experience has been so uncommon. No two stories are ever the same, even when told by the same person, and even if the exact same words are used. They are our fingerprints and we thumb them down on the pages of our lives.

That embarrassing memory – when you went on short-term hunger strike – that your brother resurrects every Christmas. That schoolyard incident – caught smoking in the bike sheds – that your classmate insists on recalling. That slice of hilarity – when the pigeon left droppings on your early bald spot – that your son chooses to tell whenever family gatherings roll around. In the process of remembering, we memorialize, delight, instruct and connect, and these stories – whether grand or trivial – change the shape of the world.

Of course, our stories can be dangerous too. They can be manipulated and twisted, but by telling them we are essentially revealing to each other that there is, after all, some meaning to why we choose to rise from the bed every morning.

Despite so much evidence to the contrary, our lives actually matter. We say to each other: Come, listen, I have something I want to tell you. Trust me, it will be worth our while.

It is 1965. They have returned to Dublin. In his job as a features editor for a newspaper he is randomly given a half-dozen rosebushes. He tries to share them with his colleagues at work, but nobody wants them. At home, he shoves the rosebushes haphazardly into the ground.

The following year they take their four young children for a stroll near the sea. They accidentally happen upon a flower show in Dun Laoghaire. It is an hour until the entries close. On a whim he speeds home, clips his own roses, puts them in a vase, drives back to the flower show, enters the competition and wins second prize.

A few months later he builds a greenhouse and begins to breed roses. Miniatures, hybrid teas, floribundas. It becomes his lifelong passion. He writes: “A man who wears a rose in his hat owns the whole world.”

One of the first roses he creates in his greenhouse is named for her: a red floribunda called Sally Mac. He will later describe it as a “Cairo red.”

The brain is a carnival when we tell our stories. According to neurobiologists, all sorts of lights erupt in our heads when we begin to make sense of our experience. In essence we are re-imagining ourselves. Neurons fire more rapidly. Synapses make shotgun connections. Our brains recreate the lived experience. Oxyctotin, the natural feel-good hormone, is released in floods, no matter if the story is happy or sad. Through the simple act of telling, we expand our mind’s potential.

But it doesn’t just happen when we tell our own stories. It happens even more spectacularly when we are listening to the stories of others. If we listen to others, we can have as many lives as we want. The miner trapped down the shaft. The woman who beats breast cancer. The child who rides her first bicycle.

In this way our lives grow bigger. Nothing creates a family quite like a story. We tell each other the things that have happened to us not only because we want to know that we’re worthwhile, but we want others to be worthwhile also. We speak, we listen, and our lungs begin to fill with the breath of life.

In the end the reason is simple enough. We are captivated by the music of what might happen next.

When all is said and done – when the last sound goes off in the darkness – everything can be taken away from us, our houses, our identities, our health, our loved ones, yet our stories about these things can never be taken away. We, like our stories, will always survive.

This is the power of story-telling and it cannot be taken from us by governments or corporations or institutions of any sort. Story-telling is our purest democracy.

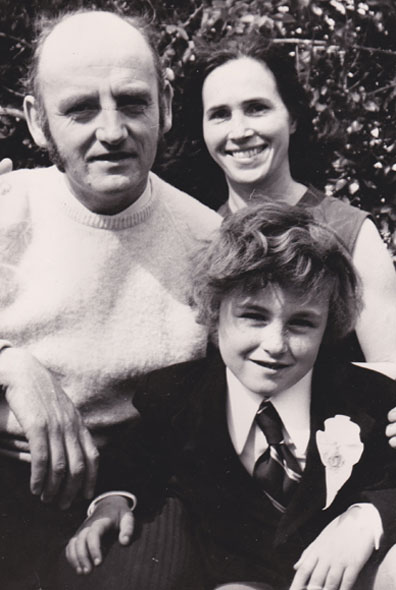

My father died in February of this year. He was 85 years old. He went gently, no tubes, no oxygen masks, no screeching late-night ambulances. Earlier, my mother sat by his bed. She sang him a song, “The Last Rose of Summer.” They had always joked that she was out of tune when she sang. Nothing could have made her out of tune this time.

Cairo. Red. He had sometimes worn that rose in his hatband.

Somewhere far away in time, but not in memory, a tent door was flapping.

This post was originally published in Oprah Magazine.