But Always Meeting Ourselves

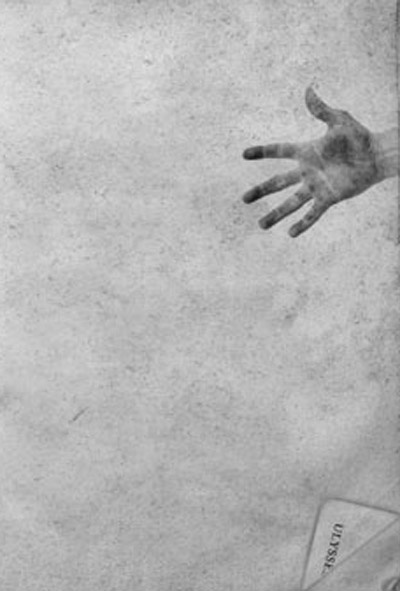

Illustration by Jamie Keenan/The New York Times

A LONDON nursing home. The shape of a figure beneath the sheets. My grandfather could just about whisper. He wanted a cigarette and a glass of whiskey. “Come up on the bed here, young fella,” he said, gruffly. It was 1975 and I was 10 years old and it would be the first — and probably last — time I’d ever see him. Gangrene was taking him away. He reached for the bottle and managed to light a cigarette. Spittle collected at the edge of his mouth. He began talking, but most of the details of his life had already begun slipping away.

Long wars, short memories.

Later that afternoon my father and I bid goodbye to my grandfather, boarded a train, then took a night boat back home to Dublin. Nothing but ferry-whistle and stars and waves. Three years later, my grandfather died. He had been, for all intents and purposes, an old drunk who had abandoned his family and lived in exile. I did not go to the funeral. I still, to this day, don’t even know what country my grandfather is buried in, England or Ireland.

Sometimes one story can be enough for anyone: it suffices for a family, or a generation, or even a whole culture — but on occasion there are enormous holes in our histories, and we don’t know how to fill them.

Two months ago — 31 years after my grandfather’s death — I got a case of osteomyelitis, a bone infection. I was admitted to a hospital in New York for a surgical debridement and a high-octane dose of antibiotics. I got a private room, largely because I’m middle class and insured, but also because it was an infectious disease. The double doors clacked when the nurses entered, visitors came and went, but for long stretches of time I listened to the ticking of a Vancomycin drip.

There is a lovely backspin in silence.

I had brought an old copy of “Ulysses,” James Joyce’s masterpiece that takes place in the back streets of Dublin on June 16, 1904. I wanted to read it cover to cover. I have been dipping into the novel for many years, reading the accessible parts, plundering the icing on the cake, but in truth I had never read it all in one flow.

The messy layers of human experience get pulled together, and sometimes ordered, by words.

Soon my grandfather was emerging from the novel. The further I went in, the more complex he got. The man whom I had met only once was becoming flesh and blood through the pages of a fiction. After all, he had walked the very same streets of Dublin, on the same day as Leopold Bloom. I began to see my grandfather outside Dlugacz’s butcher shop, his hat cocked sideways, watching the moving “hams” of a young girl. I wondered if he had a penchant for “the inner organs of beasts and fowls.” I heard him arguing with the Citizen in Barney Kiernan’s pub. I felt him mourn the loss of a child.

He walked the city alongside Bloom, then turned the corner into Eccles Street, and then another corner into my hospital room and sat on the edge of my bed. I could smell the whiskey and cigarettes on his breath.

The book carried me through to the far side of my body, made me alive in another time. I was 10 years old again, but this time I knew my grandfather, and it was a moment of gain: he was so much more than a forgotten drunk.

Vladimir Nabokov once said that the purpose of storytelling is “to portray ordinary objects as they will be reflected in the kindly mirrors of future times; to find in the objects around us the fragrant tenderness that only posterity will discern and appreciate in far-off times when every trifle of our plain everyday life will become exquisite and festive in its own right: the times when a man who might put on the most ordinary jacket of today will be dressed up for an elegant masquerade.”

This is the function of books — we learn how to live even if we weren’t there. Fiction gives us access to a very real history. Stories are the best democracy we have. We are allowed to become the other we never dreamed we could be.

Today is Bloomsday, the 105th anniversary of the events of the novel. All over the world Joyce fans will gather to celebrate the extraordinary tale of an ordinary day. There will be Bloomsday breakfasts, and Bloomsday love affairs, and Bloomsday arguments and, indeed, Bloomsday grandfathers hoisting their sons, and their sons of sons, onto the shoulders of never-ending stories.

As for me, with a clean bill of health now, I finally know where my grandfather is buried — happily between the covers of a book, where he sits, smoking and drinking still.

This article was originally published in The New York Times on June 16, 2009.