Dessert

Illustration by Tom Bachtell for The New Yorker

THE sky would always be this shade of blue. The towers had come down the day before. Third Avenue on the Upper East Side was a flutter of missing faces, the posters taped to the mailboxes, plastered on windows, flapping against the light poles: “Looking for Derek Sword”; “Have You Seen This Person?”; “Matt Heard: Worked for Morgan Stanley.” The streets were quieter than usual. The ash fell, as ash will.

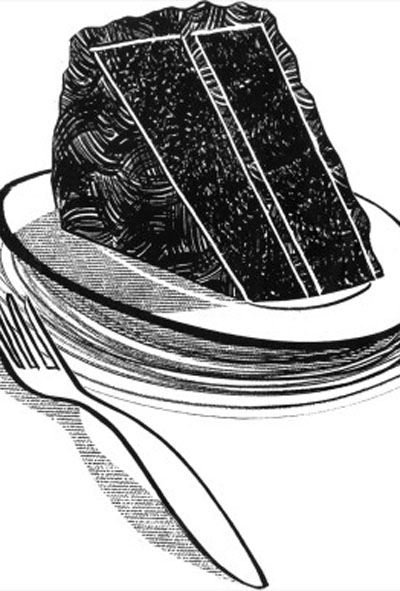

Everything felt honed down to the necessary, except for one woman who sat alone at an outdoor table in a restaurant on Seventy-fourth Street. She had just ordered a piece of chocolate cake. It arrived in front of her, and the waiter spun away. A slice of two-layer cake. Dark chocolate. A nipple of cream dolloped on top. A sprinkling of dark powder. The woman was elegant, fiftyish, beautiful. She touched the edge of the plate, brought it toward her.

At any other time, it would have been just a piece of cake, a collision of cocoa and flour and eggs. But so much of what the city was about had just been levelled—not just the towers but a sense of the city itself, the desire, the greed, the appetite, the unrelenting pursuit of the present. The woman unrolled a fork from a paper napkin, held it at her mouth, tapping the tines against her teeth. She ran the fork, then, through the powder, addressing the cake, scribbling her intent.

Our job is to be epic and tiny, both. Three thousand lives in New York had just disintegrated into the air. Nobody could have known it for certain then, but hundreds of thousand of lives would hang in the balance—in Baghdad, Kabul, London, Madrid, Basra. The ordinary shoves up against the monumental. When big things fall, they shatter into fragments. They crash down and scatter over a very large landscape. It was apparent, even one day after the attacks, that so much of the world had felt the impact.

Still, there is a need, now and always, for sharply felt local intimacies. I stood by the corner and watched the woman’s dilemma. It could have been grief, it could have been grace, or even a dark, perverse sense of humor. She held the forkful of cake for a very long time. As if it were waiting to speak to her, to tell her what to do. Finally, she ate a bite of it. She sat looking into the distance. She pulled her lips along the silver tines to catch whatever chocolate remained there, then turned the fork upside down, ran her tongue along it. It was the gesture of someone whose body was in one place, her mind in another. She pierced the cake again.

The darkness rose over the Upper East Side. The woman finished her dessert. She didn’t pinch the crumbs. She placed the fork across the plate. She paid. She left. She didn’t look at anyone as she turned the corner toward Lexington Avenue, but she still returns to me after all this time, one corner after another, a full decade now.

My mind is decorated with splinters. Ten years of enmity and loss. Bush, Cheney, Blackwater, Halliburton, Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib, bin Laden. Another long series of wars, another short distance travelled. We do not necessarily need anniversaries when there are things we cannot forget. Yet I also recall this simple, sensual moment. I still have no idea—after a decade of wondering—whether I am furious at the woman and the way she ate chocolate cake, or whether it was one of the most audacious acts of grief I’ve seen in a long, long time.

This piece was originally published in the September 12, 2011 issue of The New Yorker.