Overdue: the Country of Literature

A couple of years ago a 57-year-old in Hancock Michigan was searching through the attic of his family home, when he opened a box and a dusty copy of a book called “Prince of Egypt” fell out. He flicked to the back cover and discovered that it was a library book forty-seven years overdue. Over the years, the book had been misplaced and boxed and re-boxed and misplaced again.

The man, Robert Nuranen, went down to his local library and lay it down on the counter in front of the startled librarian. She totalled the fees and it came out to $171.32. He left the library with a receipt from a transaction that was due on June 2, 1960, when he was ten years old.

I’m not sure where I read the story, or why I remember it so well, but there are times we come upon parts of our old lives that bring us around to where we once were. John Berger has said: “If I had known as a child what the life of an adult would have been, I never would have believed it, I never could have believed it would be so unfinished.” Unfinished it always is — until it can’t be any longer. Many of us would give as much as $171.32 – if not a whole lot more – to be able to return to the past in such a small intimate manner.

I hardly know what book it was that I was reading forty-seven days ago, let alone forty-seven months. Yet the curious thing about how time eludes us is how forcefully other, more distant times actually return to us. We may not remember yesterday, but the texture of decades ago can hit us with the force of an axe.

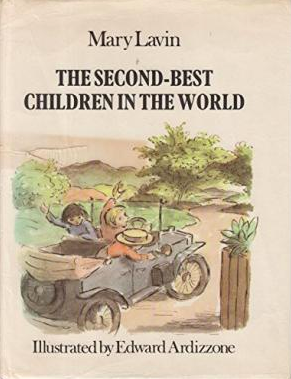

I was seven years old when I first read Mary Lavin’s “The Second Best Children in the World.” It was a book that my father, a journalist with the Evening Press, brought home to me and which he and my mother read at my bedside, but I can still remember it as if the bread is only now coming out of the oven.

I knew nothing about Mary Lavin at that stage, in 1972, but the story that she conjured up (about Ben who’s ten, and Kate who’s eight, and the other, Matt, who is “so small that I can hardly see him at all”) was powerful to me. The kids decide that – in order to give their parents a rest – they will go on a long trip around the world. As they don’t want to wear out the soles of their shoes, they walk always on their heels, but soon their shoes grow too small. They return home, having grown up and experienced all sorts of adventures, but Lavin doesn’t treat it as a moment of terror or loss. Instead, the parents come running from the house with open arms and call them the “best children in the world.” The kids disagree and their answer is a pour of cool water along the spine. Ben, Kate and Matt say that if they were the best children in the world, they never would have left in the first place. So they’re second best. And happy to be so. They have gone and they have come back changed. They would have experienced nothing if they had not left. To be best is to be static. To be second best is to slide a little knife-blade of difficulty into the journey.

It strikes me now, years later, that the book is a song for the emigrant. There is something in the emigrant’s spirit where he or she realizes that they will always, only, a form of second best. Leaving is a form of creating and instilling memory. It is also a way to inflict a damage upon oneself. Emigrants seem to want to scar themselves in order to remember where they came from. This is neither a pillar of light nor, I hope, a whine. We leave, we go away, we walk on our heels for a while, we outgrow our shoes, and occasionally we are given the grace of being able to go home.

This is what books do, also. Like countries, we leave them for a while, but having been there we are always going to come back, in one form or another. Occasionally they will sit in the attic. But they will eventually be found, one way or another. I’m happy to have stumbled upon that book forty-three years ago now.

And I’m happy to pay the fine when, in time, I too become overdue.

This essay was originally published in Brick Magazine.