The Word Made Flesh

BOXING. You can press the language out of it. The sweathouse of the body. The moving machinery of ligaments. The intimate fray of rope. The men in their archaic stances like anatomy illustrations from an old-time encyclopedia. The moment in a fight when the punches slow down and the opponents watch each other like time-lapse photographs—the sweat frozen in midair, the blood still spinning, the maniacal grin like the teeth themselves have gone bare-knuckle.

Writers love boxing—even if they can’t box. And maybe writers love boxing especially because they can’t box. The language is all cinema and violence: the burst eye socket, the ruined cartilage, the dolphin punch coming up from the depths.

Language allows the experience, and what you have with a fight is what you have with writing, and they each become metaphors for each other—the ring, the page; the punch, the word; the choreography, the keyboard; the feint, the suggestion; the bucket, the wastebasket; the sweat, the edit; the pretender, the critic; the bell, the deadline. There’s the showoff shuffle, the head spin, the mingled blood on your gloves, the spitting your teeth up at the end of the day.

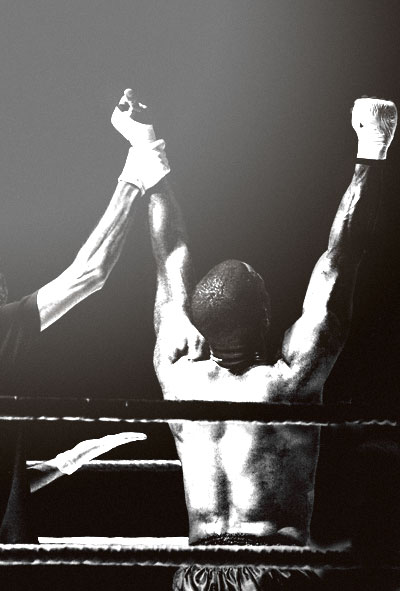

Literature re-creates the language of the epic. And what’s more epic and mythological than a scrap? For those of us who can’t fight, we still want to be able to step into a fighter’s body. We want to walk off woozy to the corner and have our faces slapped a little bit, then suddenly get up to dance, and hear the crowd roar, and step out once more with a little dazzle.

Boxers get told to imagine punching a spot behind your opponent’s head, to reach in so far so they can extend the destruction to the back of the head. Writers do the same thing—they try to imagine a spot behind your brain and punch you there. Boom. Head spin. Skin-slip on the canvas. Ten, nine, eight. Get the fuck up off this page. Four three two one Mississippi. Get the fuck up. Now.

Mailer. London. Liebling. Oates. Baldwin. Remnick. Kimball. Mencken. Who stole their title, “The Heart of Darkness”? Football has never really made great literature, nor has tennis, or cycling. Baseball and chess get a bit of literary attention, but never on the level of boxing. And I don’t know a good poem yet about curling. Let’s face it, the Great Book says that in the beginning was the word. And then the word was made flesh. And then it dwelt amongst us.

What’s most beautiful about boxing are the lives behind it. They’re so goddamn literary. Every boxer you ever met was fathered by Hamlet, and if not the Dane, well, at least Coriolanus. There’s always the Gatsby moment and the gorgeous pink rag of a suit. Every promoter you’ve ever seen has Shylock on his shoulder. You know there’s a little bit of Prufrock in that gray-haired trainer hanging out the window with all the other lonely men in shirtsleeves. And that boxing wife or girlfriend you see at home, sitting at the kitchen table, peeling potatoes, watching the clock, well, she has a little of Molly Bloom to her, doesn’t she? Later on, when her ruined boy comes home, cuckolded by defeat, she will take that bit of seed cake from his mouth.

But maybe the appeal of boxing and its own peculiar genius is that it can be used as a recurring metaphor for just about anything. Boxing is so malleable, certainly in terms of its language, that it can stand in at a moment’s notice. Boxing as economics. Boxing as supermarket shopping. Boxing as astrophysics. Boxing as a love affair. Man, she knocked me out. If you want to talk about the recent financial ruin, stroll along Wall Street and just listen to the brokers in their pinstripe dressing gowns—their takedowns, their sucker punches, their catchweights, their glass jaws, their haymakers, their throw-in of the towel on a Friday afternoon.

Boxing is your everyman, your everymove, your everything. And language understands it. Words power the punch. They also power the recovery. They paint the viciousness and then they paint the grace, or the loss, or both at once. It’s like making love with ruin, like saying: I just entered you, you soaked down in me, won’t you stay around just a little longer? We’ve all seen the peeling posters on the gym wall. We’ve witnessed the pull of the string and the click of the light bulb. We’ve heard the rear door slowly close and felt the darkness coming down. We’ve walked down through the foggy alleyway, carrying the wound, going home.

Every now and then, though, boxing moves beyond the human and just becomes plain indescribable, and you have to let the silence. You have to let it. You have to. Let it. Fall.

This article was originally published in The American Scholar on December 1, 2010 and was the foreword to At The Fights, an anthology of writing about boxing.