Looking for the Rozziner

In February 2015 my father Sean McCann passed away. This article (originally published in Granta Magazine, 2010) is reprinted here as a tribute.

Dublin in the mid-1970s. I was nine years old. It was a school day, but my father had brought me to work at his newspaper, the Evening Press, where he worked as features and literary editor. We climbed the stairs to his small third floor office. There were more books than wallpaper. On the floor, magazines and papers lay open as if speaking to each other. I sat in his swivel chair and spun. He worked on some articles, drew up a couple of layouts, ran his red pencil through a few words, his daily grind.

Outside, just barely visible through the window grime, ran the long grey sentence of the River Liffey.

Later in the morning we went to the library, the darkroom, the canteen. The further we went along, the more the building seemed to hum. We descended the stairs to the newsroom. A wash of noise – television chatter, telephones with their ringers set high, the hammer of typewriter keys. Copy boys scurried across the floor. Editors shouted into headsets. Photographers called out to one another. Pneumatic tubes ferried copy to the upstairs offices. Reporters jostled large rolls of paper into their Olympias, began their hunt and peck.

There was a raw sense in the air that anything that was ever important had happened exactly five minutes ago.

My father guided me under the fluorescent flicker, past the features desk, the news desk, the sports desk. He wore a grey suit, a white shirt, a red tie, the end of the tie crinkled where he chewed it. Messenger boys thrust envelopes in his hands. His fellow journalists looked up from their desks, nodded, winked, chatted. There were handshakes all around. Men and women ruffled my hair. At the rear of the room he lifted me up and sat me on one of the long wooden desks.

‘Listen to me now,’ he said. ‘Do yourself a favour …’

‘Yeah …?’

‘See all this here?’

I was swinging my legs off the side of the desk. He paused a moment: ‘Listen here now. Don’t become a journalist.’

He put the tail end of his tie in his mouth and chewed. Even then I knew that he was good at his job, that he was respected around the offices, and that he brought home a good wage. And I liked the music of the place, the telex machine, the Dictaphones, the carriage return bells on the typewriters, twenty or thirty of them going all at once.

‘Why, Dad?’

‘No reason,’ he said. ‘Just try not to.’

He patted the back of my head, looked away.

There was another noise in the background, a deep machine hum from the rear of the offices. My father lifted me down from the desk, took my hand and brought me back beyond the newsroom, along a stairway, through a series of swinging red doors.

The print room ran the length of a few football fields. A sort of darkness everywhere, the air soupy with ink. We moved along the metal catwalks under giant compressors and whirling fans. Conveyor belts rolled overhead. Pistons jammed back and forth. Huge cylinders of metal turned in the air.

Down on the floor of the press the pages were being laid out, the type turned backwards like some strange hieroglyphic.

My father leaned close to me and shouted something in my ear, but I couldn’t hear what he said. It was as if, by being close, he was drifting away.

He looked smaller now, in this enormous place. I held his hand as we walked through the presses. A foreman sat in a cage in the centre of the room. A thin boy passed us carrying a tray of teacups: he seemed not much older than me. Other men moved alongside us on the catwalks, shouting out to each other in the din. They looked like dark shadows, disappearing amongst the machinery.

It struck me suddenly how different these other men were to my father. A hardness about them. A rawness. They had tough Dublin accents. Their bodies took up another sort of space. They dressed differently — they wore blue overalls and flat hats. Their hands were dark with ink. My father moved softly amongst them in his well-tailored suit. Nobody laughed or joked or ruffled my hair. We went along the metal catwalk, following the line of a newspaper all the way back to the guillotine, where the papers were stacked and bundled and thrown into the rear of vans.

Outside, another hubbub. Motorcyclists. Delivery boys. Security men.

The news of the day to a boy nine years old was how very big the world suddenly was, and how very different men could be, and how people seemed to have their own little corner, and every corner was a world.

I glanced at my father, standing in the sunlight on Poolbeg Street, and it was something akin to growing older, something akin to moving away.

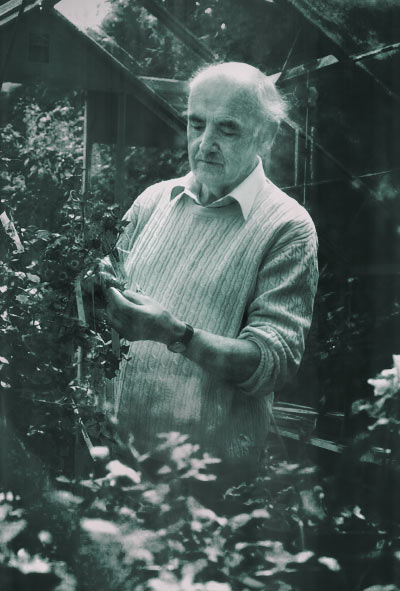

I grew up in the suburbs of south Dublin. My father had a rose garden. One thousand roses so closely packed together that you could smell their fragrance fifty yards up the street. He would put in his shift at the newspaper and then drive home, pour himself a glass of wine, and walk out the back door to go and talk with his roses. It was his moment of release: the necessity of a toil beyond words. Later he would pull on his old fur-lined boots, his Garden News anorak, his old torn trousers, and he would dig, or he would mow the lawn, or cut the hedge, or fix the greenhouse windows, or cross-pollinate the seeds he had so carefully nurtured.

He worked the soil as if he wanted it to tire him out.

Twice a year we would get a load of manure from a nearby farm, to fertilise the roses. It was dumped, stinking, in a heap in our front garden. It could be smelled a hundred yards up the road. My father liked nothing more than pulling on his boots and taking out a shovel, loading wheelbarrow after wheelbarrow, pitching the manure into the flowerbeds. My brothers and sisters tried to avoid the day when the shit arrived, just so we wouldn’t get called into service.

Once we found a tiny dead calf in the manure, no bigger than a shoebox. My father tossed it away and happily went back to work.

He grew floribundas. He developed brand new breeds of miniatures. He labelled and bred. He pruned the stems back. He weeded. He trimmed the edges of the beds. He squashed greenfly between his fingers. On summer nights he would stay out until the sky folded dark above him. On weekends he would spend his whole day in the garden or would take us down to Dun Laoghaire for a flower show.

There was one other passion too: football. He had been a professional footballer for Charlton Athletic when very young and although it pained him to think of his roses getting smashed he still allowed us to play football in the garden. He even set up a net by the berberis hedge. My brothers and I hammered the ball back and forth. It was impossible to protect the roses, of course. They were always going to get walloped. When the ball hit a stem, I would run inside to find a roll of Sellotape, and try to bring the broken ends together, even braid the leaves and branches around one another for support.

Once my father clipped a broken rose and brought it in to my mother to put in a vase, the tape very carefully removed

Thirteen years later, I got the chance to watch the printers at work again. I was a junior reporter then and still young enough to get a thrill from watching one of my stories roll off the presses.

I walked down from the newsroom and stood on the metal catwalk.

I generally tried to avoid my father while I worked: not for any reason other than the simple fact that I wanted to avoid the talk of nepotism at the newspaper. I had gotten the job fairly and squarely – I had even won a Young Journalist of the Year award – but I had no desire to hear the begrudgery. And there was always his admonition in my ear: Don’t become a journalist. And the older I got the more I realised how important my father was in Dublin literary circles. He was known for taking on young writers. He had created a special page for women journalists only, something quite radical at the time. He paid everyone well. He encouraged people. He had even started, along with David Marcus, the New Irish Writing Page that had published everyone from Edna O’Brien to Ben Kiely to John McGahern to Neil Jordan.

I stood one afternoon in the printing room and saw him coming down the stairs towards what was known as the stone, where the paper was laid out. He moved through the inky dark. He had a pencil behind his ear and a metal ruler in his hands. He seemed to wear the same grey suit he’d worn years before. His tie was still damp where he still chewed it. I had fallen in love with language by then and there was nowhere better than the printing room for words: The hellbox, the Devil’s box, the slugbox. The widows, the orphans, the slugs. The galley, the stick, the guillotine.

I recall thinking: there is my father down amongst the stone men.

His pages were set and ready for printing. He read them for errors and style. He could read both upside down and backwards. Years of practice had made him fluent at reading any way he wanted. I watched as he finished his work, carefully and meticulously. He stuffed some papers in his brown briefcase and left. Headed home, no doubt, towards his roses.

When their shift ended, a group of printers – compositors and proofreaders – trudged out the back door, onto Poolbeg Street. I fell in behind them. I don’t know why I wanted to follow, I just went on instinct. There was a sort of melancholy in me – I was thinking of leaving Ireland at the time, giving up my job, going to America, maybe even going away to try to write a novel.

It was a short trip down to Mulligan’s, a beautiful old pub that sat behind a 200-year-old facade. The printers knew the place well. They walked in through the haze of cigarette smoke and sawdust. The printers didn’t know me – I was just another face in the crowd. I sat nearby and listened. Someone called out for a rozziner. ‘Give us a rozziner there, will ya?’ The word was repeated a couple of times, the hard Dublin music of it.

‘What’s a rozziner?’ I asked one of the men.

‘The first drink of the day,’ he said.

It took me years to figure out that they were talking about the rosin that goes on a violin bow before playing.

If play is the shadow of work, then maybe work stands in the shadow of play.

In early 2009, I went back to Dublin from my home in New York. My father’s garden was in good shape to an amateur eye, but for him it was a disaster. There was simply too much work to do. Some of the rosebeds had been dug up and gravelled over. The soil was choked in weeds. The hedges were tatty. He looked out of the kitchen window, his face drawn long by the fact that he couldn’t nurture the place anymore.

He was long retired from the newspaper. In fact, the newspaper itself was long retired from the world – the whole Irish Press group had gone bankrupt in the 1990s.

I went outside and started to pull up the weeds. The work felt fresh to me. My father stayed at the downstairs window most of the time, but by the end of the first day he was outside, standing on the doorstep.

‘Would you stop doing that for crissake?’ he said, looking at the deep cuts on my hands, my arms, my scalp.

The next day he stood out in the garden, leaning on a blue walker in a light rain, as I ferried in among the roses, getting thorned again. ‘It’s looking better,’ he said, ‘but jaysus you don’t have to do it, we can hire someone in, you’ve got other things to do. Just leave it.’

The next day he had a glass of wine in his hands. On the fifth day, when the garden had begun to look fresh – and therefore ancient – my father got down on his hands and knees and started weeding in the flowerbed alongside me.

It may have stretched towards parody – bygod the man could handle a shovel, just like his old man – but there was something acute about it, the desire to come home, to push the body in a different direction to the mind, the need to be tired alongside him in whatever small way, the emigrant’s desire to root around in the old soil.

A month later, back in New York, I ended up with a case of osteomyelitis, a bone infection that laid me up in hospital for a couple of weeks. Morphine every morning, an odd rozziner. And then two more months of antibiotics.

The doctors said I had possibly gotten the illness from a recent wound.

It was likely, they said, that some dirt got into a cut on my hands, that it had migrated to my blood, my tissue, my bone.